Get Inked: The History of Japanese Tattoos

By Malia & Tehya

As one well-versed in Japanese culture may know, tattoos are still a very taboo subject in Japan. Most foreigners living here have them, yet a fair amount of younger Japanese (in Tokyo and Osaka) have them as well, so the times are changing, albeit quite slowly. (Hey, that’s Japan!) Still, it is still against work dress code to have them showing in the office; gyms, onsens, and pools still reject people who have them showing; and (usually the elderly) will show their displeasure at sighting one in public, especially if on a foreigner. Because of their association with the Japanese yakuza, tattoos have remained taboo.

However, although tattoos only recently became legal again, Japan has a long history with them.

Irezumi is the Japanese word for tattoo and refers to a distinct type of tattooing. They’re created through a process called tebori which means “to carve by hand.” A piece of metal or wood was used to tap ink into the skin via one or a group of needles. Initially, these tattoos were made with the same tools used to create wood engravings, chisels and burins. Chisels were adapted into needles that would be grouped together according to the desired thickness for the lines. The tattoo specialist, known as horishi, would then test the needle by sticking it in his own skin. If the needle would stick, then he would attach it to a long piece of metal and the end of the needle stick would be tapped by a hammer, repeatedly plunging the needle into the skin. It was an extremely painful process.

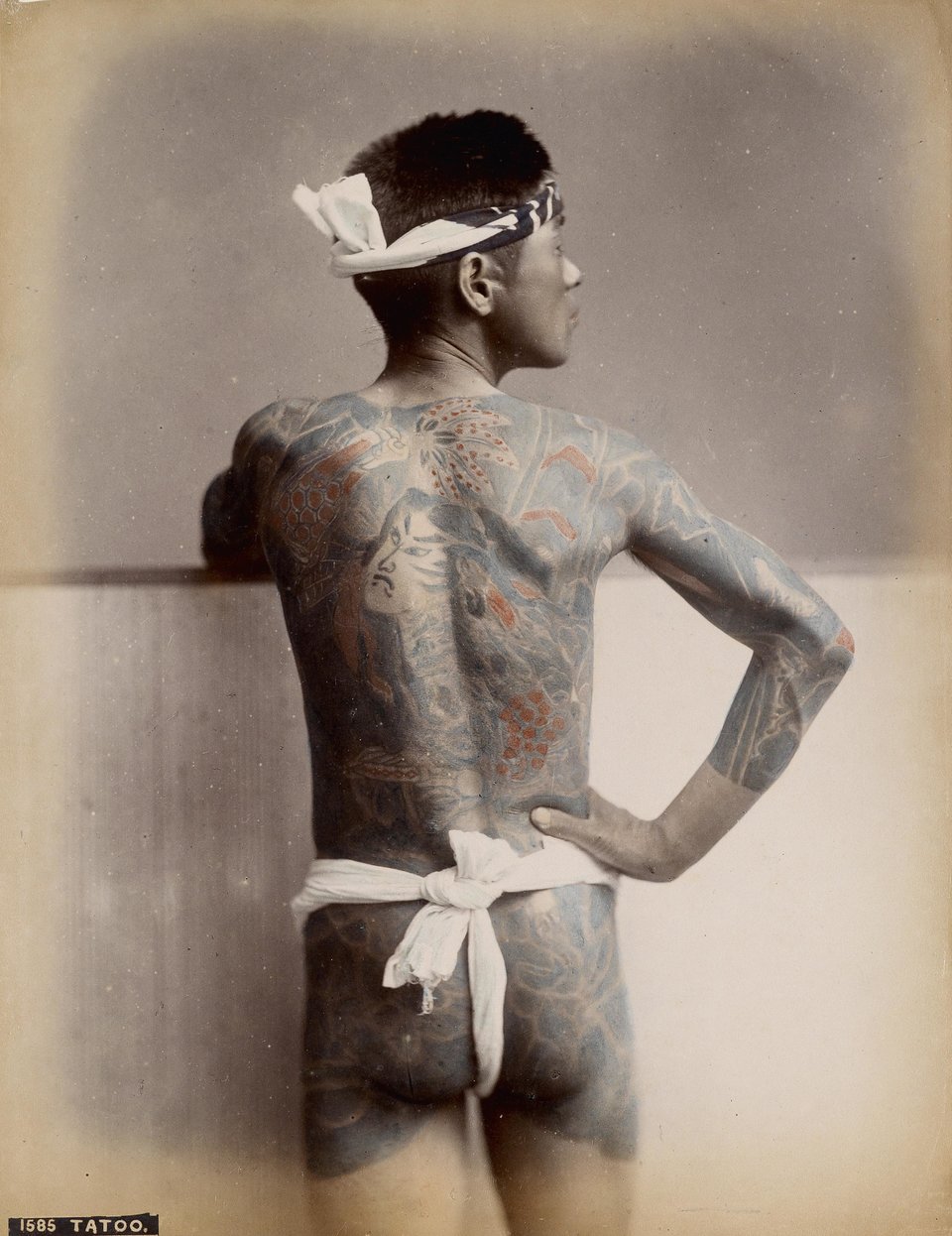

The ink used was also unique to the irezumi process. The first color and ink was called “Nara ink,” also known as “Nara black,” which was produced from soot collected from temple lamps. It was known to turn greenish-blue after being injected into the skin. Later on, other colors like indigo, yellow, green, and red were developed, with red being the last and most dangerous. Red ink was made from incredibly toxic ingredients that could cause illness, fever, and even death. Only a few places could be tattooed in red.

Japanese tattoo history can be traced all the way back to the Jōmon period from 10,000 BCE-300 CE. The Jōmon people had their own complex culture and language that would form the foundation of contemporary Japanese culture. Evidence of tattoos from that period was found when archaeologists excavated pottery from that time. The Jōmons were really into pottery. Little figures called dogu were discovered that had markings all over their faces and bodies. Et voilà, the first evidence of Japanese tattoos!

Further evidence of Japanese tattooing was found in the third century by Chinese merchants and emissaries who traveled over to the land of “Wa” (the Chinese name for Japan at that time). They discovered men with fish, shells, and other ocean motifs covering their bodies. When the Chinese inquired about these markings, the fishermen revealed that their tattoos were meant for protection against the giant legendary man-eating fish that lived in the Sea of Japan. A fisherman’s gotta do what a fisherman’s gotta do to protect himself and his livelihood. The Chinese visitors recorded this experience in the Gishiwajinden, the oldest Chinese record of encounters with the Japanese.

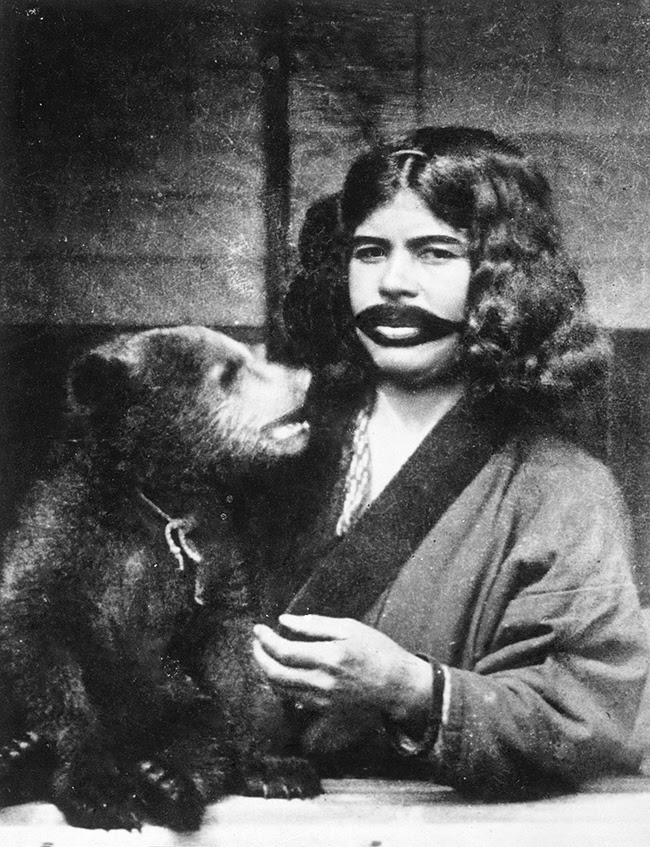

The image that most people think of when the subject of Japanese tattoos is brought up probably looks something like this: an almost naked man with slick black hair, a scowl on his face, and his body completely covered in dragons, koi fish, and waves. This image isn’t wrong but it’s not the only tattoo style that originated in Japan. The Ainu are one of the two indigenous tribes of Japan. Their territory once spread from Hokkaido to Tokyo, but now they mainly reside in Hokkaido due to their land being snatched from them during the Meiji Restoration. (Sound familiar?) The Ainu have a truly unique culture that differs greatly from the rest of Japan. The most distinctive differences are their facial and hand tattoos. Similar to the Samoan style of tattooing, Ainu women have large smile-like tattoos covering their lips and chin, as well as several tattoos covering their arms and fingers. Although men are also tattooed, women are the predominant carriers of tattoos. The method of tattooing is very similar to that of irezumi, with the exception of the mouth tattoos; these are done using scarification and rubbing the ink into said scar.

The tattoos themselves are connected to the Ainu animistic religion and healing practices. A tattooless Ainu could not enter the afterlife. Some tattoos are for protection, while others mark important events in a person's life, and are also used as a form of social identification. When an Ainu person got sick they would be encouraged to get a tattoo in a specific place to encourage healing.

The indigenous Ainu still live in Japan but the tattoo culture was badly affected by discriminatory policies starting in the Edo period. The biggest issue emerged when Japan was trying to homogenize and create a single, unified Japan—any deviation was unacceptable. One policy stated, “regarding the rumored tattoos, those already done cannot be helped, but those still unborn are prohibited from being tattooed.” In 1871, the Hokkaido Development Mission, a group dedicated to “taming” the “wild” (not today, colonizer) Hokkaido people proclaimed, “those born after this day are strictly prohibited from being tattooed” because the custom “was too cruel.” Ainu women continued to tattoo themselves in secret but the punishment and social exclusion proved to be too much. The practice died when the last tattooed Ainu woman passed away in 1998.

Governments have a knack for transforming a beautiful cultural element into a form of ridicule and punishment. The Edo period was a time of massive reform and unification in Japan. Militant leader after militant leader was in charge of the country and they were ruthless in cracking down on crime and punishment. A defining moment in the history of Japan was the decision by lawmakers to make a person’s crimes public, meaning the tattooing of that person's crimes on their forehead. And thus, the shame-based society of Japan was born. (And still thrives today!) Different crimes were associated with different kinds of forehead tattoos. The kanji for dog (犬 / いぬ) was a popular tattoo for petty crime. With each offense committed, another line was added, and four crimes would complete the kanji. Another popular kanji was 悪, meaning bad.

So while the Edo government was criminalizing the Ainu for their tattoos, they were literally marking criminals with tattoos. However, as soon as something is deemed off limits or subversive, people are naturally going to rebel. Soon after tattoos were established as a form of punishment, they turned into a new form of self expression.

It is common knowledge that tattoos couldn’t be removed (in pre-laser removal times), but tattoos can be covered up. People quickly discovered that a small kanji tattoo could be turned into a large decorative piece. Decorative tattooing had coincided alongside punishment tattooing for years, and as soon as people discovered that their criminal tattoos could be covered up with beautiful artwork, the punishment of tattooing essentially became meaningless. By the end of the 17th century, the government had to find new ways to punish people.

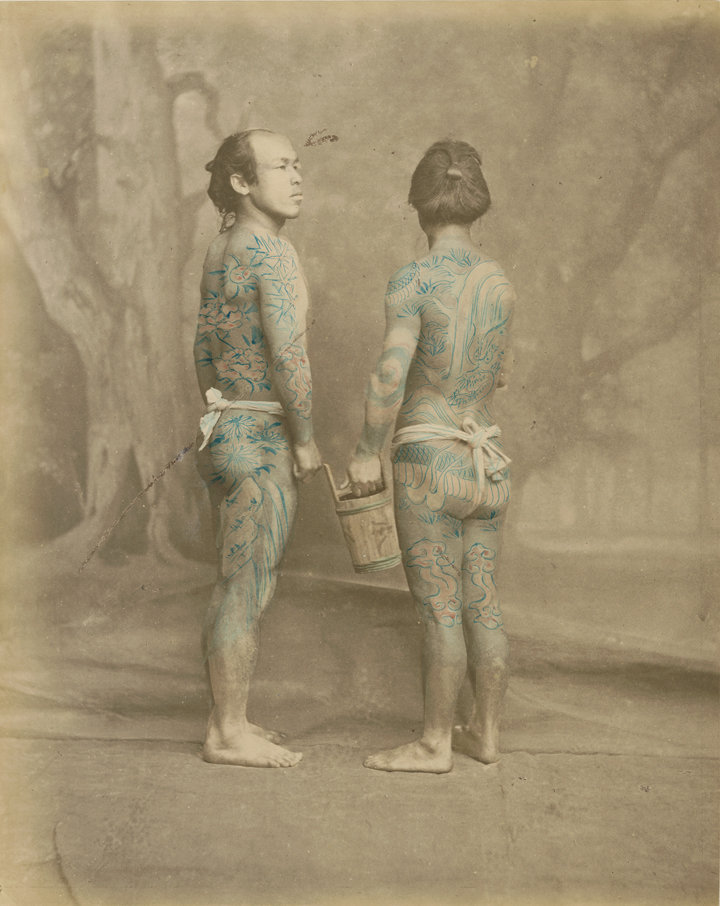

Decorative tattooing flourished behind closed doors, as it had grown and progressed so much that rules, traditions, and special meanings developed alongside these masterpieces. The first style of tattoo was done only on the back. Gradually, tattoo designs extended to the shoulders, arms, and thighs, and finally, tattoos began to appear on the whole body.

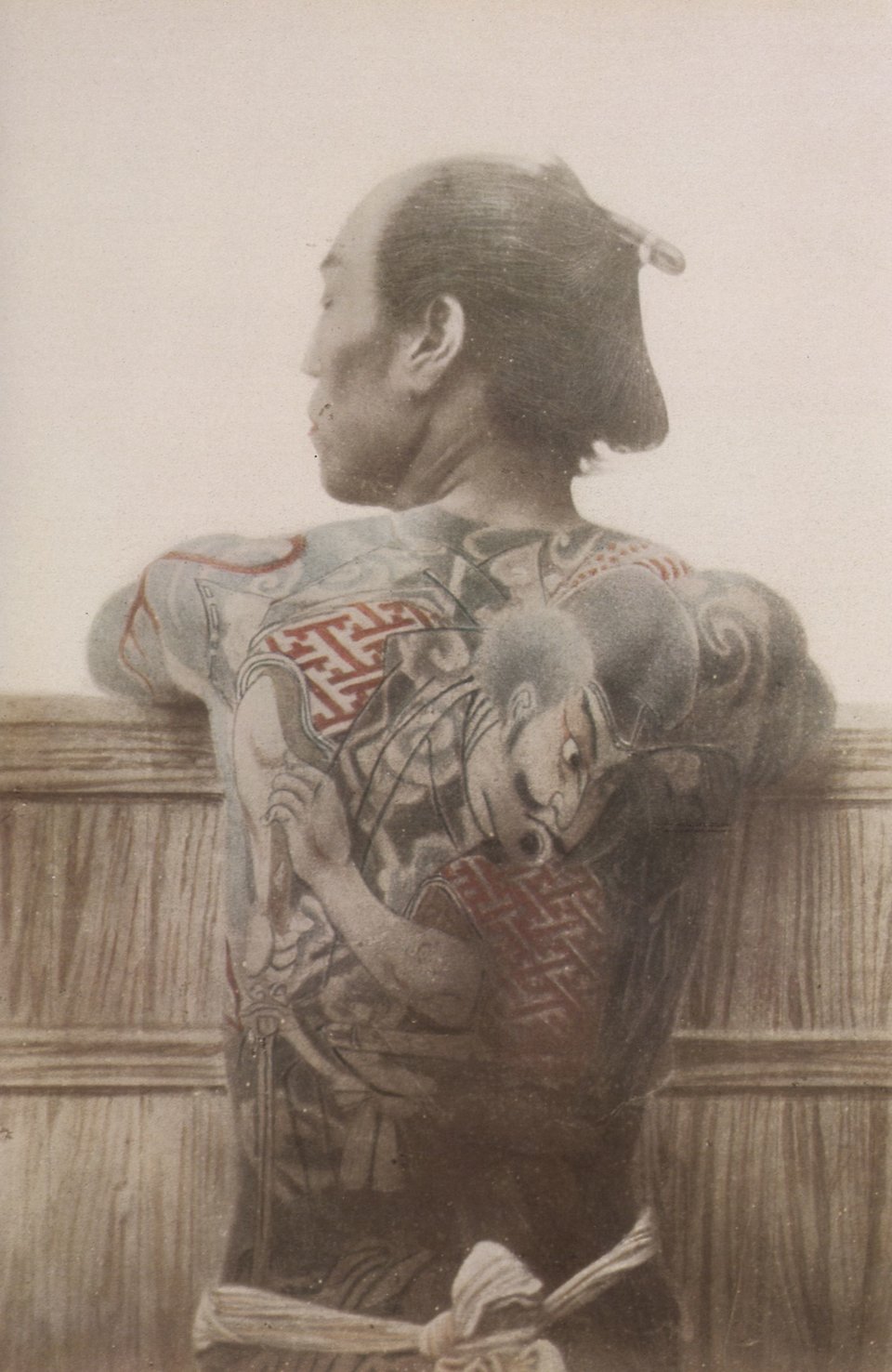

The irezumi that has now been associated with the yakuza consists of a single major design that covers the back and extends onto the arms, legs, and chest. The design requires a major commitment of time, money, and emotional energy. The idea of the full body tattoo came from samurai warriors’ costumes called jimbaori, a sleeveless campaign coat worn over armor. It looked like a vest and was easy to slip on over armor. With the establishment of the yakuza also emerging in the Edo period, the yakuza and tattooing went hand-in-hand, changing and developing together.

In the Edo period, kabuki theater and woodblock printing called ukiyo-e became another popular artform that both influenced and was influenced by yakuza irezumi. Artists making posters for kabuki theater and woodblock printings were influenced by the art of tattooing from an 18th century novel titled Suikoen. The main characters of Suikoen all had elaborate descriptions of full-body tattoos, and just like the year after Frozen came out and everyone wanted to be Elsa and Anna, everyone wanted to emulate these impressive badass heroes. Ukiyo-e artists in particular really influenced the art of tattooing. In fact, tattoo artists themselves never designed the tattoos. Instead, the ukiyo-e artists would create the design. The tattoo artist would simplify it to fit the body and ukiyo-e artists would paint the design on the client's body using ink. The tattoo artist would then take over and make it permanent. The clientele of these woodblock tattoo artists were 80% yakuza.

One would think that the motifs chosen for their body suits would be about blood and monsters, but due to the influence of ukiyo-e artists that wasn't the case. Balance and harmony of the seasons was, and still is, the main focus of irezumi tattoos. Artists would meet with their clients several times and would then make a design for the client based on their personality and standing in the yakuza. Within these designs are some harmony constants:

Spring themes must be with spring

Winter with winter

Fall with fall

And summer with summer

For example, one cannot have a snake with cherry blossoms because snakes hibernate in the spring, when cherry blossoms bloom. One can’t have roses and koi because they both signify a new beginning, which isn’t balanced. The most common and potent combination of animals is the tiger and dragon, in Japanese this combo is called ryugo. The tiger protects against demons and disease, while the dragon brings good fortune. There are thousands of combinations that can be found.

So why were the yakuza so drawn to tattoos initially? Of course, there’s the criminal aspect, but is that really a good enough motivator for expending so much time, money, pain, and emotional effort? No, of course not! There are three main reasons given for the yakuza tattoo love connection. They cost a serious amount of money, so if someone could afford to get a full body tattoo by an affluent artist then clearly they will be making bank. A tattoo is one of the clearest and most permanent, if not the most permanent way, to show commitment to the group because it’s perpetual and non removable. These tattoos are also insanely painful, so if someone is able to sit through a full body of this pain, then they are clearly not to be trifled with. Because of the last two reasons given, tattoos became a kind of initiation or weeding out process for various yakuza groups. A good majority of people who start the full body tattoo will never end up finishing it, and if they didn’t finish it they were no longer a welcome member.

For non-gangsters, tattoos in contemporary times have come to represent both personal and cultural signifiers. Both authors of this piece have three tattoos each. Malia has a pineapple with tribal print to signify her family and Hawaiian heritage; a female symbol to signify her identity as a strong and empowered feminist; and a Picasso line drawing from a French poem (which she translated before getting it tattooed) to signify her love for art and history. Tehya has swallows and gardenias, with swallows to represent her four great loves in life and the final one to represent her finding her freedom, and the gardenia for her grandfather; an ohm symbol to remind herself that she has the power to keep her inner peace, and the word “serendipity” because it’s her mom’s favorite word.

Tattoos carry history, cultural history, personal history, and world history. Every tattooed person carries these stories within their skin. Something as simple as a tattoo can carry the weight of generations of ancestors or the burden of a criminal cast out from society—so much can be learned from these fleeting pieces of art.

Resources:

Brian Ashcraft & Hori Benny, Japanese Tattoos: History * Culture * Design (2016); “The Ainu: Reviving the Indigenous Spirit of Japan”; “The Smiling Tattoos of the Ainu Women”; “The Meaning of Tattoos for Ainu Women”; “Ainu People Today: 7 Years after the Culture Promotion Law”; “Tattooing Among Japan’s Ainu People”; “A History of Japanese Tattooing”; “Inked and Exiled: A History of Tattooing in Japan”; “A Guide to The Mythological Creatures of Japanese Irezumi”; “Japanese Tattoos History and Meaning”; “Understanding the Language of Irezumi”

Images: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons; Image provided by Tehya N.; Image provided by Malia O